Archived Newsletter Re-Post.

The AOX Newsletter • April 2024 #16

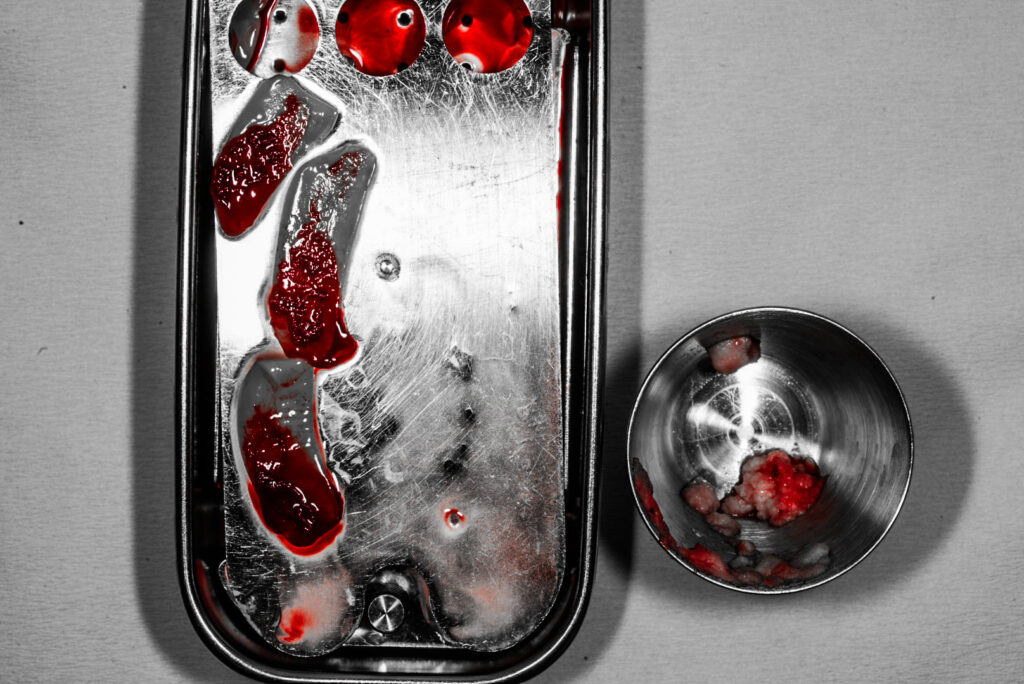

One of the many benefits of All-On-X surgery is that it is typically a graftless procedure.

That being said, there are no absolute rules regarding when to graft and when not to graft. And, in discussing AOX grafting with providers, I have noted that there are many different opinions surrounding this topic.

Some providers feel that every socket should be grafted and “preserved” after implant placement to allow for better maintenance of overall bone volume. On the other hand, many feel that an AOX surgeon should avoid grafting at virtually all costs and use a remote anchorage site as an alternative instead.

I am definitely not here to tell you what is right or wrong. And, in reality, I fall somewhere in between those two ends of the spectrum. While I will perform selective AOX bone augmentation, it is not common that I graft during All-On-X surgery. And today, I’m going to discuss why that is the case.

4 Reasons Why I Don’t Routinely Bone Graft During AOX Surgery

1. I believe it is simply unnecessary most of the time.

All-On-X surgery was created, in part, to avoid the need for bone grafting. Routinely performing extensive grafting (i.e. every socket) is, in my opinion, voiding one of the most beneficial aspects of this procedure.

Furthermore, I do not feel that grafting every socket provides the patient anymore benefit and at times can actually negatively impact the patient’s healing course.

AOX surgery has been performed for years now, by surgeons all over the world. Consistent success, integration, and long term implant health have been documented – without the routine need for extensive grafting.

After having completed 2,297 arches to date (updated for re-post) – I have also noted that in my hands, consistent grafting during AOX surgery is not necessary for long term, successful surgical outcomes.

2. Graft material leads to increased inflammation at the surgical site.

In my experience, placement of a graft increases inflammation at the graft site. I feel this is even more pronounced with non-autogenous bone.

Why is this important?

With extensive grafting, patients often experience a notable amount of increased swelling and therefore increased post-op pain. Plain and simple – these patients are more swollen and in more discomfort after surgery.

Furthermore, with increased inflammation at the wound site, these patients present with more pronounced tension at the wound margins and a higher risk of post-operative incision line dehiscence.

3. Graft material can lead to an increased infection risk.

Any time we add another element, or foreign body (more notably non-autogenous bone), to a surgical site – we are creating a possible source of infection.

Does this mean that we should never graft or that grafts always cause infection?

No. That’s not at all what I’m saying.

However, before adding a potential foreign body to a surgical site – we need to ask ourselves the benefits it provides relative to the risks we are incurring on behalf of the patient. If we cannot rationalize a strong benefit for the graft – should we do it at all?

4. Increased cost to the practice and patient.

Non-autogenous grafts will increase surgical overhead. This will either be passed on to the patient, to the practice, or both.

While this is not a reason not to perform a graft that is actually indicated – this is, in my mind, a good reason not to perform a graft that is NOT indicated.

Grafting in the setting of AOX surgery does, at times, absolutely have its place. However, in my practice I do not routinely graft as I feel this voids some of the significant benefits this procedure provides and adds, often unnecessary, increased post-op surgical risks for my patients.

“To graft or not to graft” – that is the intra-operative question.

Matthew Krieger DMD

P.S. I would like to add that I am not opposed to grafting and that, while not common, I do use strategic bone augmentation during AOX surgery.

Check out this week’s upcoming blog post to read about “6 Scenarios in Which I Prefer to Bone Graft During AOX Surgery”.

“There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.”

Peter Drucker

Q & A with Dr. K

“How do you measure VDO intra-op when the patient is swollen?“ |

The first step is having an accurate pre-op skeletal VDO provided by my prosthodontist. We attempt to use skeletal reference points, as these are more easily reproducible in surgery.

Swelling of the soft tissues can affect the accuracy of purely soft tissue measurements.

Because of this – efficiency is also key. I will attempt to have both jaws reduced and ready for “VDO Check” within 30-45 minutes. If it is taking 3 hours to get to this point – there will definitely be more soft tissue edema.

With both jaws reduced, upper and lower surgical guides representing the desired reduction numbers (the guide is normally ~15mm in height), are placed in the mouth and the patient is closed into the planned bite.

A Venus Gauge (known also by other names such as an Apollo Gauge) is then used to confirm the planned VDO. In order to be as accurate as possible, skeletal reference points Me (Menton) and A Point are used. These are essentially the base of the bony chin and the base of the bony nasal spine.

The gauge is applied to the outer soft tissues but depressed firmly until bone is palpated. The measurement is taken at this point (both pre-op and intra-op).

If the VDO is not accurate – adjustments are made either surgically or prosthetically as needed prior to moving on to implant placement.

*Note: While this is a great question that I wanted to respond to – this is also a complex topic difficult to address in one short response. VDO assessment and management is an important topic that will be covered in detail in my upcoming course).

*Update since original newsletter:

I have flip flopped back and forth over my career from doing one jaw at a time, to performing both at once. Since the writing of this newsletter, I have gone back to performing one jaw at a time. I cut the maxilla first to completion and then the mandible. While there are benefits to doing both jaws at once… I simply find one at a time less stressful.

In this scenario (one jaw at a time), the upper guide has a fixed reference point – the palate. So reduction can accurately be checked using this fixed and reproducible anatomic point. The maxilla is cut to completion using this reduction reference. Then, attention is directed to the mandible. After mandibular reduction, the VDO gauge is now used to check intra-operative VDO as described above with the upper and lower guides in place.

Archived newsletters are released on a delayed timeline, a few months after the original publication. If you would like to receive these newsletters in real time please sign up here.