I am not a fan of traditional surgical guides in the setting of All-On-X surgery.

Not even a little bit.

To be fair, while I have seen traditional AOX reduction and implant guides used, I have never actually used either myself. So, you can argue that I haven’t fully experienced traditional AOX guided surgery.

However, when I have seen traditional guides used by other surgeons, I am always perplexed at how popular they are despite being incredibly cumbersome, inefficient, at times expensive, and all the while providing quite frankly – little to no value.

I realize that’s quite a controversial statement.

While you in no way have to agree with my thought process, I want to ask that you think outside the box for the next 5 minutes and genuinely ponder the points I am about to make.

If you do so, and you wish to return to your traditional surgical guides – I can respect that.

However, many of you may very well find yourselves ditching the deceptive facade of comfort provided by your traditional guides – for a superior level of Graphite-Guided Surgery.

Below are 6 reasons “Why I Love Graphite-Guided All-On-X Surgery”. So get comfortable, and if you feel like taking notes, reach for that #2 pencil…

Why I Love “Graphite-Guided” All-On-X Surgery

1. Graphite-Guided Surgery is adaptable. Traditional surgical guides are restrictive.

Great All-On-X surgeons understand the value of being highly adaptable. If we want to be able to immediately load cases, we will be forced to frequently adjust our game plan intra-operatively.

We should not be focused on blindly following a guide. We should be focused on solving the overall problem at hand – how to immediately load the patient in our chair with a full arch fixed prosthetic.

In order to do this we need the “full arch” at our disposal, not just a few pre-determined ideal sites.

As the Navy SEALs say, “No plan survives first contact with the enemy”. It is no different in AOX surgery. We should have a plan, but we should be ready to adapt the minute that plan does not survive.

We simply cannot easily adapt with a traditional guide. And if we are adjusting intra-operatively during traditional guided surgery, we are typically tossing the guide aside and not using it at all…

2. Graphite-Guided Surgery is as accurate, if not more accurate than traditional surgical guides.

This one really gets me.

The biggest pushback to Graphite-Guided Surgery is:

“It’s impossible to make sure your bone reduction and implant placement are accurate without a real guide!?”

Here is a response and explanation to the statement above:

How is a traditional guide created?

The restoring dentist (or surgeon) determines how much restorative space they need from the incisal edge of the dentition (or alveolar crest if edentulous) during the prosthetic work up. This reduction number, typically 15-18mm in the anterior with some taper posteriorly, is then passed along to a company that fabricates the reduction guide. Or, the treating doctor might use this reduction number themselves to create their own guide if they have a printer.

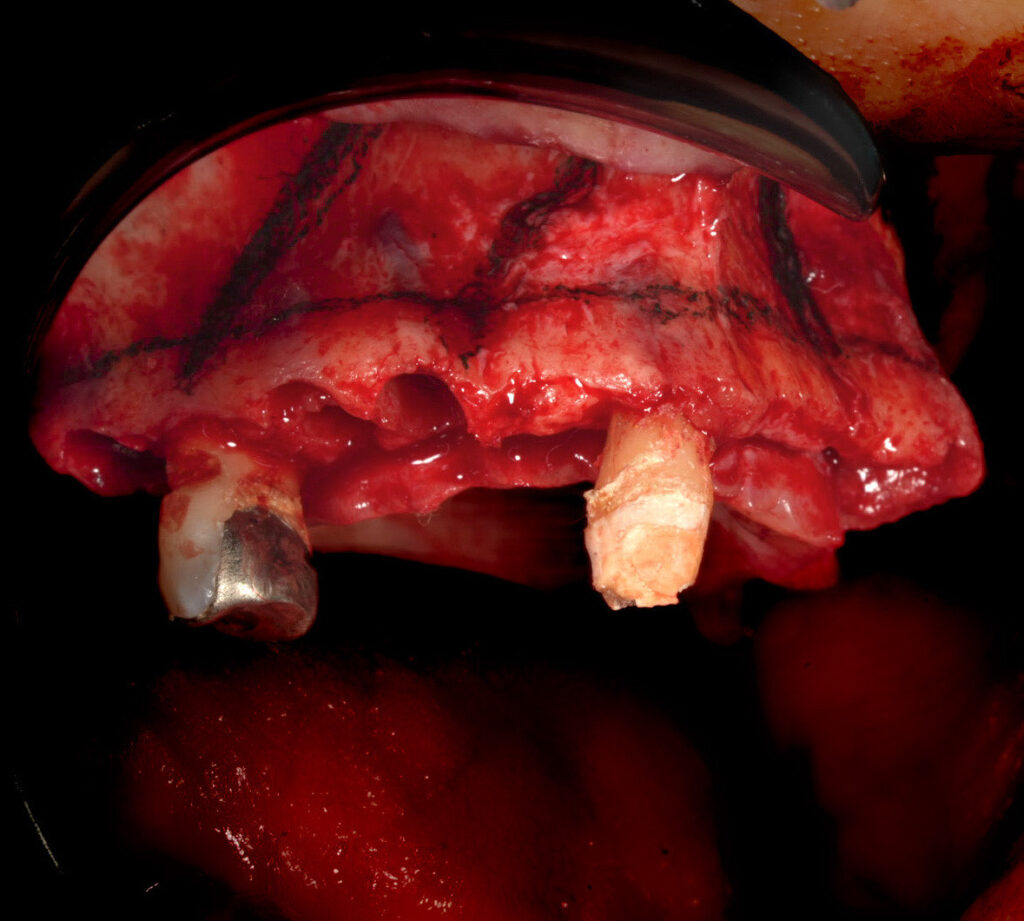

Once fabricated, what is the reduction guide?

The reduction guide is essentially a digital line drawn across the arch to the proposed reduction measurements that the doctor provided. This guide is then placed intra-operatively to provide the surgeon a visual representation of the “digitally drawn line”, which simply indicates how much bone to remove.

This digital line is only as accurate as the initial measurements and work up. Meaning if the work up is off – the guide is of no value.

So we can agree then that the value in this “line” is really the accuracy of the prosthetic work up, and not actually some mysterious magic of the “guide” itself.

Therefore, if we are confident in our workup and the need for, let’s say 15mm of reduction, we simply need to find a way to put a line at 15mm from the incisal edge of the dentition.

One way is a potentially expensive, cumbersome, printed guide that needs to be screwed or fixated in place and that furthermore, may be inaccurate if not seated properly.

A second option, is a $0.10 pencil that allows us to mark our own line exactly 15mm from the incisal edge of the desired teeth.

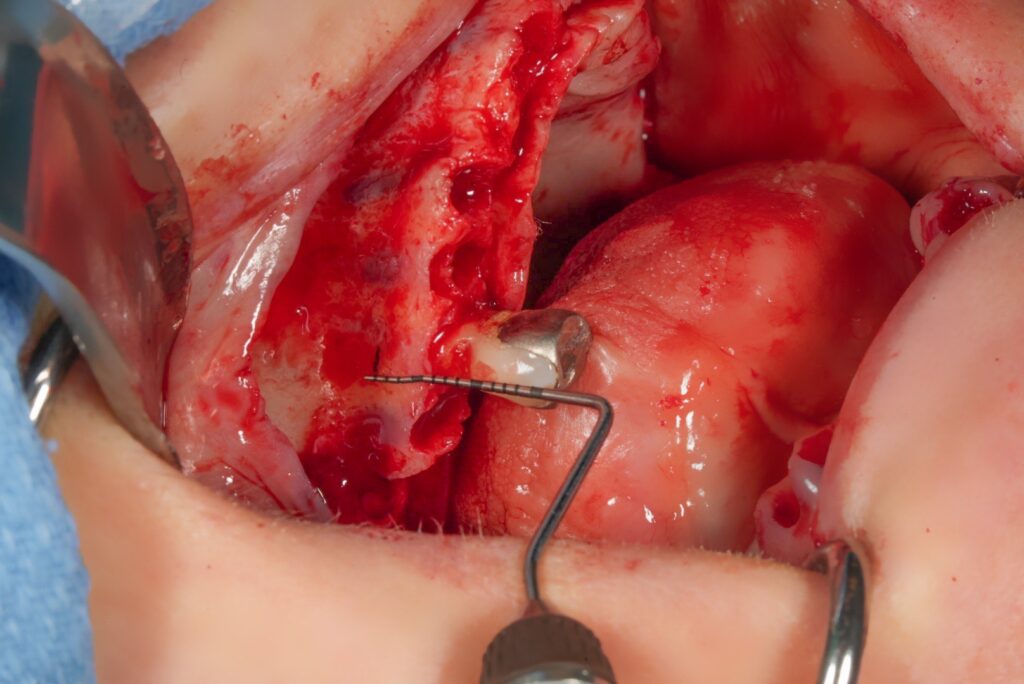

We can measure this with a perio probe or ruler, and we can check it and re-check it if we’d like. It is literally the most accurate measurement we can get. If we simply carry this line across the arch, we have our reduction guide. A guide that is arguably more accurate, with easier intra-operative confirmation than a traditional guide.

Placement of implants is no different.

We must remember that in AOX surgery we can literally visualize virtually every important anatomic structure when our flap is reflected; the mental foramen/nerve, the nasal cavity/piriform rim, even the extent of the sinus if you want to transilluminate and/or access via a small window.

Following an assessment of the panorex and CT scan we should be able to accurately “draw” our implant placement and angulation at the precise position that we want for an optimal surgical outcome.

Again, this is what a traditional guide is doing for us… digitally. And this traditional guide is extremely beneficial in implant surgery where we have limited vision or no vision at all of the surrounding bone and adjacent anatomic structures.

But in AOX surgery, we have the unique advantage of literally staring directly at all of these anatomic landmarks. They are right in front of us. This allows us to create our own intraoperative, accurate, easily visible guide with a surgical graphite device.

While it takes both practice and surgical hand skills to master this technique, the basis of creating a uniform, symmetric, accurate surgery with surgical adaptability – is simply drawing an accurate line… and then following it. That’s it. That’s the magic.

3. Graphite-Guided Surgery is more efficient and less expensive than traditional surgical guides.

Graphite-Guided Surgery Total Cost: $0.10.

Total Time to Implement Guide: ~10-15 seconds.

Traditional Surgical Guide Total Cost: $25-50 if a printer is owned by the practice and/or anywhere from $200-600 dollars per arch if an outside company is fabricating the guide.

Total Time to Implement Guide: *Pre-op digital planning/meeting and submission (15 min to 60+ min) plus an additional ~5-10 min per arch for proper utilization and verification of seating.

Cost and efficiency should not be the main reason we utilize graphite guided surgery.

If I felt a traditional guide was a better surgical option for my patients and myself, I would use one. Regardless of the increased cost and time.

However, given that Graphite-Guided Surgery is arguably better suited for AOX surgery than traditional surgical guides, it makes no rational sense to pay more for a traditional guide and then spend significantly longer trying to utilize it intra-operatively. Not to mention, this increased surgical time also adds to assistant and anesthesia overhead and puts the patient through a longer general anesthetic procedure.

4. AOX surgery has built in flexibility via MUA prosthetic components. This is optimal for the intra-operative adaptability of Graphite-Guided Surgery.

Single implant and “non-arch” related implant surgery demand precision for an optimal prosthetic outcome. Believe it or not, I am a fan of traditional guides for single implant placement.

On the other hand, full arch surgery has a decent amount of surgical and prosthetic flexibility, given that implant angles and positions can be corrected and adjusted via different MUA angulations. Furthermore, even if an access hole is not in an “ideal” position, it does not mean that the prosthetic is not clinically acceptable.

I know what you’re thinking. Ok, so this guy just does surgery that’s barely clinically acceptable because he doesn’t use a guide.

That’s not what I’m saying. No one’s perfect, but the vast majority of my surgeries exhibit precision and symmetry with the use of Graphite-Guided Surgery.

My point is, that if for all the reasons above Graphite-Guided Surgery is just as accurate (if not more accurate) than traditional-guided surgery, AND we technically do not even demand exacting precision in AOX surgery – then, why in the world are we using a restrictive traditional guide?

Couple this with the fact that I have seen multiple “traditional guided” surgeries with less than ideal, asymmetric implant positions and poorly positioned screw access holes creating large, unpleasant lingual and palatal flanges for patients. Clearly a traditional guide does not make everything “perfect”.

5. Graphite-Guided Surgery has a much higher probability of immediate loading.

The adaptability and ease with which intra-operative adjustments can be made, make Graphite-Guided surgery far superior in the setting of All-On-X full arch immediate loading.

Delayed loading is not in any way wrong. There are times where it is indicated and there are even a subset of patients that may truly be better served with this option. However, most patients have come to understand and prefer “immediate loading”, for obvious reasons.

When speaking with colleagues who exclusively utilize traditional surgical guides for AOX cases, I notice that there is a higher incidence of delayed loading. This is, in my opinion, due to the fact that the guide is followed meticulously. And, if composite torque is not adequate, the decision is made to bury the implants. There are no “intra-operative adjustments” made. It is assumed that the bone is simply too “soft”. While this again, is not wrong, this is the false assumption that the guide is providing a service – when in reality it is prohibiting the surgeon from adapting and loading the case.

Some surgeons also plan to only delayed load their prosthetics. In this setting, the referral, patient and surgeon are all on the same page. So this is a well received and acceptable option. This is also a highly predictable option, not dependent on insertion or composite torque. In many ways, I am envious of this scenario.

In this delayed load scenario, you can argue that traditional surgical guides are the better option. And, you may be right.

For those practitioners, however, that work in a “full arch center” and/or market “next day teeth”, delayed loading isn’t ideal. It’s not what this style of practice advertises, and except in rare cases, it is not why the patient is coming into the practice in the first place.

In these clinical settings, ultimate flexibility and intra-operative problem solving are necessary to ensure the patient is able to receive an immediately loaded prosthetic.

If the composite torque isn’t adequate, it’s my job to find a way to make it adequate. If A-P spread isn’t what I thought it was going to be, it’s my job to look for additional implant placement. If a buccal plate fractures, it’s my job to move or re-direct an implant. These on-the-spot adjustments are simply too difficult day in and day out with a traditional implant guide.

While I am a proponent of both the use and advancement of technology in oral and maxillofacial surgery, at this time, Graphite-Guided Surgery is still the mainstay in the world of All-On-X for predictable immediate loading.

6. Graphite-Guided Surgery rapidly improves a surgeon’s skillset and ability to problem solve, while traditional surgical guides impede the growth of an AOX focused surgeon.

In 2015, I was approached to help with full-time coverage of a local All-On-X center. It was an incredible opportunity.

I turned down that position.

To be honest, I was scared of AOX surgery and didn’t understand it.

One of the deciding factors was that upon my visit to the center, I was utterly shocked that they were doing AOX surgery without a traditional guide.

I hadn’t done any AOX surgery at this point in my career, but I had done a fair amount of guided single implant surgeries. I had been well trained to use a pre-fabricated metal tube to tell me where to place my implant. I couldn’t comprehend how to work without this and how, quite frankly, this was even allowed in cases as extensive as AOX surgery?

I walked away from that offer feeling like “I was a better surgeon, with higher standards, and better surgical results than they could provide”.

5 years later I went to train alongside that same surgeon who I would have worked with, at least for a short while, in that center. He was, and is, one of the most highly trained AOX surgeons in the world, with thousands of arches under his belt.

What an opportunity I wasted. And in large part, because I ignorantly thought I was “better”.

In reality, I lacked the surgical training, confidence and ability to “adapt” in the way that AOX surgery demands.

Despite being a well-trained oral & maxillofacial surgeon, I did not have the confidence and skillset to operate without a guide. I was guide dependent… I had A LOT to learn.

After finally making the jump in 2019 to full-time AOX surgery, I quickly learned the value in using Graphite-Guided Surgery.

AOX surgery is unpredictable – plain and simple. There are countless times that intra-operative adjustments and changes are required to immediately load.

Experiencing this firsthand, I shifted my focus to mastering Graphite-Guided Surgery and I grew quickly as an AOX surgeon. I became more confident. I became a better problem solver. I became adaptable. Ultimately, I provided a better surgery to my patients.

In my opinion, Graphite-Guided Surgery not only produces a better surgical result, it also produces a better surgeon.

When we envision “guided surgery”, we almost all think of a large acrylic piece of surgical instrumentation. We have been engrained that this is the standard of care. While this may be the case in many aspects of oral & maxillofacial surgery – I do not feel that this is the case in the setting of immediately loaded full arch surgery.

Remember that a traditional guide is, in essence, creating a digital version of an intraoperative pencil line. You can use either. But it is far more efficient, more adaptable, and in my opinion actually more accurate to use the $0.10 pencil.

When asked why I don’t guide my surgeries, my response is always the same:

“I do guide my surgeries. I perform highly accurate, adaptable, Graphite-Guided Surgery.”

And it’s the truth.

I hope this article helps “GUIDE” you down the right path.

Matthew Krieger DMD

P.S.

If you are debating whether or not you can or even should use a sterile pencil in surgery – don’t bother looking up the term “Graphite-Guided Surgery” – I have made this term up. But – I feel it is quite catchy. I will, however, reference you to a *plastic surgery article below reported in 2020 that comments on the benefits of intra-operative graphite use for surgical marking, as well as a secondary **reference to craniofacial and maxillofacial surgeons using pencils for intra-operative bone marking.

P.P.S.

I want to reiterate that this article is solely in reference to All-On-X surgery. Furthermore, it is in reference to surgeons who desire to immediately load their AOX cases. It is my opinion that traditional surgical guides for single unit implants, implant supported bridges, and over dentures can provide great benefit. There is less prosthetic flexibility in these scenarios, inadequate direct surgical visualization, and the need to immediately load is not present. This is an optimal setting for the use of a traditional guide.

References:

*Bharathi Mohan P, Chittoria RK, Gupta S, Aggarwal A, Reddy CL, Shijina K, Pathan I. Innovative Use of Graphite Pencil in Cranioplasty. World J Plast Surg. 2020 Jan;9(1):104-105. doi: 10.29252/wjps.9.1.104. PMID: 32190602; PMCID: PMC7068182.

**Melnick, Meredith. TIME Magazine. IKEA Pencils: The Latest in Surgical Technology. December 10, 2010. https://healthland.time.com/2010/12/10/ikea-pencils-the-latest-in-surgical-technology/

Great article!

Thanks Stanley! Appreciate it! Glad you enjoyed it.

How do you go about determining/verifying your reduction level in an edentulous patient?

Hi Stanley,

This is a great a question! In order to give it an adequate and detailed response I will address this in an upcoming newsletter in the Q & A section!

Thank you!

Out of curiosity, have you ever had a case where you had to replace a failing implant and seen your previous pencil markings in place still? Interested if the angled graphite markings would degrade quickly.

Hi Josh,

Good question. In my experience, while I have occasionally seen minor remnants of markings (especially if a surgical site was very quickly re-visited), the majority of the time the markings are not clearly present. The graphite is easily removable at the time of surgery and normally washes off with irrigation and suction. I would add that I specifically allow my markings to be washed off/suctioned via surgical suction. I do not “try to have them remain”.

Keep in mind that one of the benefits and part of the safety profile of a sterile graphite device, as has been shown in multiple literature articles, is that it does in fact wash away easily. It’s not permanent. This is a known advantage of it. I use it as a “temporary” sterile intra-operative marker for reduction and normally my posterior implant sites. In reality, I only need it to be visible for a couple of minutes. I know that it will wash off with irrigation/suction, but I am only using those references for key points, and for a short period of time during the surgery.

So I do buccal reduction fairly quickly because of the marking so I know how much to reduce. I, along with other clinicians I’ve heard, tend to not reduce enough on the lingual initially, and then I go back several times until I have enough reduction – big time waste. Any tricks to being able to “eyeball” the flat reduction plane quicker, or does that come with reps?

Hey Shaun,

First of all – you are absolutely correct. Almost all providers, including myself, have the tendency to under-reduce on the lingual. This is likely due to the natural position of our hand/arm when holding the handpiece. Furthermore, our “line” is on the buccal so it can be deceptive to think just because we have reduced to the line on the buccal, that it is the same position on the lingual.

I noticed this problem many arches ago and have corrected it in the following ways:

1. I know that it is a problem, so I intentionally focus more reduction on the lingual. Clinically I “feel” like I’m reducing more on the lingual, but I know inherently that I am not – it just “feels” that way.

2. I stand at 12 o’clock when doing the maxillary reduction and look directly down on the arch. It is pretty clear and easy to assess symmetry from this vantage point. While reducing from this view I start at the midline (after gross bone removal with the double action rongeurs) and move to my left toward the posterior, **sweeping palatal to lingual. Most docs start on the buccal because that’s where the “line” is. I start on the lingual and sweep toward the buccal line. *In this way my lingual always has to be at least as reduced as my buccal. Once the left side is done I move to the right side. Here I start at the canine region and again, “sweep back” toward myself from lingual to buccal – extending back to the midline. Finally I move to the premolar region and sweep lingual to buccal moving posteriorly toward the tuberosity. *This can be done many ways – I think the key in my hands is reducing the lingual portion first with the sweep of my bur and assessing the reduction looking directly down from the 12 o’clock position.

3. I reduce in a similar fashion (lingual first) on the mandible. The only difference here is that I stand at the 7 o’clock position (obviously we cannot stand at the 6 o’clock position. I then try to look directly “down” the mandibular arch to assess symmetry from this vantage point (while not as common – if uncertain I will also assess the mandible with a quick glance from the 12 o’clock position while moving the mandible up toward the already flat/symmetric maxilla for comparison).

4. I do both jaw reductions prior to implant placement in a double jaw. So both bone shelves are visible at the same time. As mentioned in the last point – this allows you to compare the symmetry of each to one another and can definitely be helpful in achieving a symmetric, flat bone shelf.

Hope this helps –

Brilliant! Thank you!

i love it , one of my reasons for guide , is for the angled posterior implants upper and lower , i find it difficult to make osteotomy that is 30 degrees of so and be in the center of ridge buccolingually at the apical level of the implant , i usually start and in middle and while drilling the implant may lean toward lingual or buccal , i am worried to perforate through lingual or buccal , any advice to be close to accurate , like my position or drill position ,

thank you Matt

Hey Joseph,

1. First all of this takes practice and reps. Most of my implants are pretty symmetrical – but they aren’t “all” that way. I have times where I think I’m placing or drilling at a slightly different angle than I actually am. In reality this usually isn’t a clinical issue but nonetheless – I have to constantly pay attention to that angulation.

2. As mentioned in a previous article, I often drill “slowly” – this is for many reasons but one of which is that if the tip of your drill perforates out either the lingual, the buccal, or into an anatomical space like the nose – you will actually feel this “drop” and loss of bone contact. If you are drilling at a high speed you cannot feel this. While it’s not ideal to perforate, if you do with your starter drill, simply re-direct and maintain a bony stop with your new trajectory. Then follow your “new” trajectory with your subsequent drills.

https://aoxsurgery.com/why-i-drill-slowly-benefits-of-the-low-rpm-osteotomy-technique/

3. I use a perio probe after each drill to feel and confirm that there is in fact a bony stop. If there’s not – I assess why and correct.

4. Ensure you can visualize the buccal extent of your osteotomy path with your flap reflection so that you can actually see a perforation. On the lingual, more so the mandible, take your finger and palpate down in the floor of the mouth and feel the trajectory of the lingual aspect of the mandible. Sometimes there will be a lingual undercut that you need to be aware of that is more pronounced than others.

*Biggest piece of advice: Visualize the buccal, palpate the lingual, and drill slow feeling for a bony stop the whole way.

Hope that helps –

thank you , that is very helpful

Thank you Joseph!

Pingback: My Preferred Bone Graft for AOX Surgery - AOX Surgery

Pingback: 5 Reasons Practitioners Get Frustrated with Full-Arch Surgery - AOX Surgery

Where do you buy your graphite pencils?

Hi Dr. Falender, I will email you a link. Thanks for reaching out.

Matt

Can you email me the link to?

I have an issue with my marks getting washer away during the surgery. Any tips?

Sure. Keep in mind that one of the benefits and part of the safety profile of a sterile graphite device, as has been shown in multiple literature articles, is that it does in fact wash away easily. It’s not permanent. This is a known advantage of it. I use it as a “temporary” intra-operative marker for reduction and normally my posterior implant sites. In reality, I only need it to be visible for a couple of minutes. I know that it will wash off with irrigation/suction, but I am only using those references for key points, and for a short period of time during the surgery.